How to write a plot twist

But first, a personal anecdote.

I was in Vegas for a friend’s wedding and we stopped at a bar on the strip for shots. My group (all women except me) was approached by a fast-talking street magician. He was convinced he could fool us. We were skeptical but it was a vacation so we indulged him. At the time, I had this oversized Diesel watch with an led display. It was heavy, so I’d notice if I lost it, right?

He was a fast-talker and a comedian who kept us fully engaged with a series of swift movements I can barely remember. At some point, he turned my barstool around while I was in it. At the end of his routine, he retrieved my watch from my friend’s cleavage. I had not idea my watch was gone; she had no idea it was in her shirt.

I’m not sure of the exact point in my drafting of Gorgeous I decided to have a twist but I think it was pretty early on. The reason the twist works so well is because I knew readers would go into it believing it was one kind of story when it turned out to be another. That’s the slight of hand necessary for executing a twist — you have to get the reader comfortable and constantly reinforce and distract them with the thing they’re comfortable with. That comfort convinces them they know where things are going, all the while you’re dropping hints to the reveal that don’t look like hints. I’m referring to this as a skill in retrospect; I was not a skillful enough writer at the time to have a master plan. I was coasting on vibes.

Another anecdote, this time involving my favorite show Melrose Place. Get comfortable for a blitzkrieg of “context” and spoilers for a 30 year old show.

The show started in season one as a spin-off of Beverly Hills 90210 with straight-forward earnest storylines about 20-somethings figuring their lives out. Every episode was fairly self-contained, and corny. If anyone wants to get into Melrose, you have to suffer through season one to appreciate what came after. It sets the stage for what makes the events of season two so impactful. Two major additions happened during the first season:

Marcia Cross as Kimberly Shaw

Heather Locklear as Amanda Woodward

These characters brought romantic intrigue, villainy and cliffhangers. By the end of season one, Jane learned her husband Michael had an affair with Kimberly. Early in season two, in the midst of his divorce from Jane, Michael proposes to Kimberly just before their car goes off a cliff. Kimberly dies offscreen. The “twist” happens late-midseason across three carefully written and marketed episodes.

S2E26 - In Bed With the Enemy: Amanda, Melrose Place’s landlord, hires a property manager, a pervert who cuts holes in the walls to spy on tenants. By this time, the show was leaning into it’s psychosexual nature and audiences were expecting something hot an depraved. The previews for the following episode promised Amanda would catch and maim him.

S2E27 - Psycho Therapy: Amanda does catch him and much of the third act centers on whether or not she’ll kill the guy. This is what the marketing promised for an entire week. Audiences were comfortable with a shocking resolution to this storyline. Amanda let the guy go, but at the very end our attention is pulled to another storyline. This one involves Michael, who’s now in a relationship with Sidney. As they toast to their happy (and depraved) relationship, the camera pulls back to a figure waiting outside the house. It’s Kimberly, very much alive.

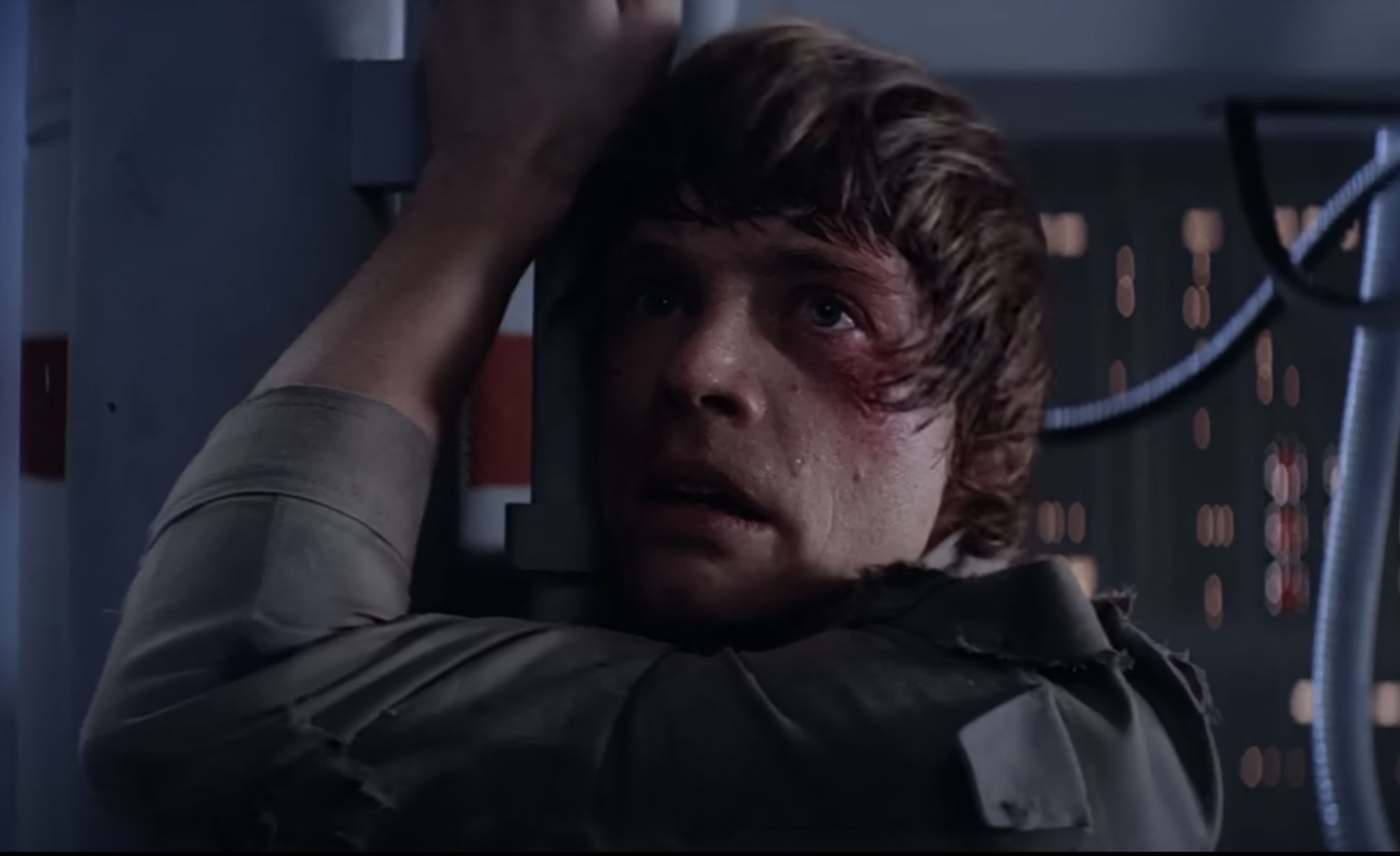

S2E28 - The Bitch is Back: The Kimberly reveal worked for two reasons: One —although the show was getting soapier, audiences weren’t prepared for a return from the dead. Two — the marketing and tension leaned heavily towards the storyline involving the perverted property manager. But the writers weren’t done with us. In episode 28, Kimberly is back in Michael’s bed. After making love, the twist gets twistier, where she goes to the bathroom and tugs her hair. The hair we’ve always known is a wig, and underneath is an ugly scar. This is one of the most shocking moments in TV history because of it’s impact and current memeabililty.

This was 90s network television. Melrose ran roughly 40 episodes per season with no repeats. Audiences had to be tuned in and wait week to week for their answers.

Me and my friends in Vegas were comfortable with the style of interaction we expected from the magician, which set the stage for the surprise at the end. Melrose audiences were already expecting something cool to happen in season two, but not Kimberly’s wig. For Gorgeous, I established a story about four archetypal friends in the city navigating love, friendships and work, a formula audiences were comfortable with because of Sex and the City, Waiting to Exhale, Noah’s Arc, etc. But it turned out to be something else.

I’d argue there’s no exact science to it, but the skill of a plot twist is to show audiences the thing they’re too comfortable with was a lie the entire time.